Indo-Pacific Coral Reefs are Disappearing More Rapidly Than Expected

31 Aug, 2007 10:49 am

Until now, we knew very little about geographic and temporal patterns of coral loss in the Indo-Pacific, which contains 75% of the world?s reefs and is the global center of marine biodiversity. Results from a paper recently published in PLoS One indicate that coral loss in the Pacific began earlier and is far more rapid and geographically extensive than anticipated. These results were based on 6001 quantitative reef surveys of 2667 individual reefs. The results augment a new, quite dismaying view of global coral reef decline and have significant implications for policy makers and resource managers.

Scientists, sport divers and conservationists have known for several decades that coral reefs are in trouble. But until recently, we really didn’t know much about regional or global patterns of coral loss: when it started, how fast it is happening, and which parts of the world are most affected. In 2003, a group of scientists led by Isabella Côté (now at Simon Fraser University in Canada) published a landmark paper in Science, documenting coral loss throughout the Caribbean (Gardner et al. 2003). This gave the coral reef ecology and conservation community the first glimpse of how changes that had frequently been observed on particular reefs, were playing out across an entire region. The team estimated that the annual rate of coral cover loss in the Caribbean between 1977 and 2001 was approximately 1.5%, with the greatest decline occurring during the 1980s.

Unfortunately, we still had no idea what was happening on 90% of the world’s coral reefs. My graduate student Elizabeth Selig and I decided to quantify coral loss in the Indo-Pacific. This region, stretching from French Polynesia in the east to the Island of Sumatra in the west, encompasses approximately 75% of the world’s coral reefs and includes the center of global marine diversity for several major taxa including corals, fish and crustaceans. At the time, the project seemed fairly straightforward, but it turned out to be anything but.

Collecting the coral cover data for the database, that eventually included 6001 quantitative surveys of 2667 reefs performed between 1968 and 2004, took us over three years. Each individual survey measured the percentage of the bottom covered by living corals, which is a metric of reef health analogous to the coverage of trees as a measure of tropical forest loss. Much of the data came from federal institutions like the Australian Institute of Marine Science and organizations like Reef Check, which trains sport divers to perform basic surveys of reef health. But a lot of survey data also came from scientific literature, which we obtained by searching libraries, journals and other databases, and extracting the necessary information from each article. The results of our analyses were quite surprising.

We found that the rate and extent of coral loss in the Indo-Pacific are far greater than expected (Bruno and Selig 2007). Coral cover was also surprisingly uniform among subregions and declined decades earlier than previously assumed, even on some of the Pacific’s most intensely managed reefs (i.e., Marine Protected Areas). Surveys conducted during 2003 indicated that coral cover averaged only 22.1% (95% CI: 20.7, 23.4). Our estimated annual coral cover loss was approximately 1% over the last twenty years and 2% between 1997 and 2003 (or 3,000 km2 per year), which is approximately five times the net rate of tropical deforestation. Additionally, the spatial patterns of coral reef degradation are very different from rainforest loss in that nearly all reefs have been affected and there are virtually no remaining pristine reefs. Twenty years ago, high cover reefs were common. But today, very few reefs in the Indo-Pacific (only about 1-2%) have coral cover close to the historical baseline of roughly 50%. Describing the generally bleak picture to NationalGeographic.com, Dr. Nancy Knowlton, a professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography said, "It was assumed that the Caribbean was the worst case scenario…But ignorance is not bliss."

One piece of good news is that that coral communities are still resilient, often returning to their original live coral cover ten to thirty years after major disturbances. So they still have the ability to recover, possibly quite rapidly, if we can reduce some of the major stresses responsible for global coral loss. Reversing coral loss will require actions across a range of scales including: (1) local restoration and conservation of herbivores that facilitate coral recruitment and the reduction of fishing practices that directly kill corals, (2) the implementation of regional land use practices that reduce sedimentation, and (3) the institution of global policies to reduce anthropogenic ocean warming and acidification. The challenges are clearly significant but so are the stakes. Like many of my colleagues I am optimistic that we will solve this problem over the next few decades.

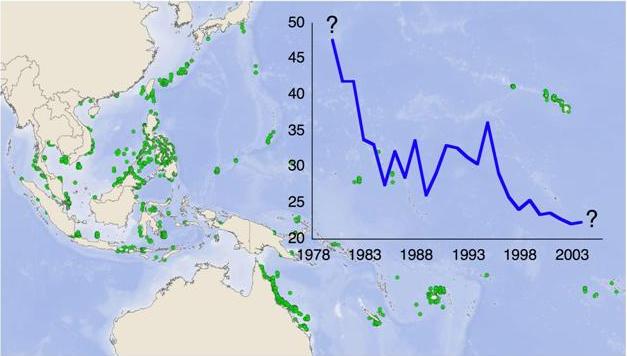

Figure: Map of the Indo-Pacific study region. Green dots are the reefs that were surveyed between 1980 and 2004. Inset graphic illustrates the loss of coral (left axis is the percentage of the bottom covered by living corals) over a 25 year period. There is substantial uncertainty about regional reef health in the 1970s and about the historical baseline of coral cover before humans began altering reefs across the region in the 20th century. There is also no way to know what the near-term future of reefs will be. There are some reasons to be optimistic, but plenty of reasons to expect further loss. Some of the main causes of coral loss include outbreaks of predatory starfish and infectious diseases, destructive fishing techniques, poor land use practices and coral bleaching caused by especially high ocean temperature.

Credit for graphic: J. Bruno and E. Selig. Data are based on Bruno and Selig 2007

References:

Bruno JF, Selig ER (2007) Regional decline of coral cover in the Indo-Pacific: timing, extent, and subregional comparisons. PLoS One 8:e711

Gardner TA, Côté IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR (2003) Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science 301: 958-960

Further resources on this and related research

Link to the paper at PLoS One (an open access journal)

-

16/07/09

Global conservation priorities based on human need

-

08/06/09

Tropical forests worth more standing

-

25/11/08

The Island Rule: Made to be Broken?

-

03/10/08

Marine reserves and climate change: study finds no-take reserves do not increase reef resilience

-

26/09/08

The Rockefeller Foundation and climate change

Read more

Read more

The actual results are presented all too briefly. They should be presented in greater detail. The elaborate exposition on socio-economic implications of the results should be made more succint.

[Response] Thank you Dr, Gadgil for your suggestions. I substantially edited and rearranged the article: -I shortened the socio-eco implications section and and moved it up to the top -I expanded the results section Sincerely, John Bruno