Parasite Hijacks the Mind of its Host

17 Apr, 2007 06:08 pm

It sounds like something from a science fiction film: a parasite that enters the brain and manipulates the behaviour of its host. But this is not science fiction - it?s very real. The parasite is a unicellular organism called Toxoplasma gondii, which ?hijack[s] the mind? of its host, according to Ajai Vyas, lead author of a paper, published online last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describing the effects of T. gondii infection on the behaviour of rodents.

Normally, rodents have a aversion to the smell of a pheromone found in cat urine, for obvious reasons. This aversion is innate - rodents fear the smell of catsí urine even if they have never encountered it before, so this fear seems to be hard-wired. In 2000, researchers from the University of Oxford discovered that T. gondii manipulates this fear behaviour - infected rodents are mildly attracted to, rather than averse to, the smell of cat urine. This is a case of fatal attraction - of course, attraction to the smell of catsí urine makes infected rats and mice more susceptible to predation, thus increasing the probability that the parasite will complete its life cycle.

Vyas and his colleagues presented infected and uninfected rodents with a series of choose tests. The animals were placed in an enclosed circular area that had been divided into four sections. One of the sections was laced with bobcat urine, another with rabbit urine. The amount of time spent by each group of animals in each section of the area was then measured. Sure enough, in confirmation of the earlier findings, it was found that infected animals spent far more time than uninfected ones in the section laced with bobcat urine. T. gondii infection had effectively abolished their aversion to the odour of the urine, and made them mildly attracted to it instead.

The animals were then trained to fear a region of their enclosure. On several occasions, they were placed in the middle of the arena, where electric shocks were administered to their feet. When this was repeated a number of times, the association of the middle of the arena and electric shocks was strengthened, and the animals displayed fear behaviour - standing still - when placed in that part of the enclosure (i. e. the animals had been classically conditioned to fear that part of the arena). When tested later, both infected and uninfected animals froze when placed in the centre of the arena, because they expected to receive a shock to their feet. Infected animals also remained fearful of the odour of foods they had not encountered before, and still became anxious when placed in an open space. Infected rodents continued to exhibit other anxieties and are still capable of learning to fear other stimuli. Thus, rather than altering the hostís sense of smell, or having a generalized effect on fear behaviour, T. gondii specifically targets and modifies the response of rodents to the smell of cat urine.

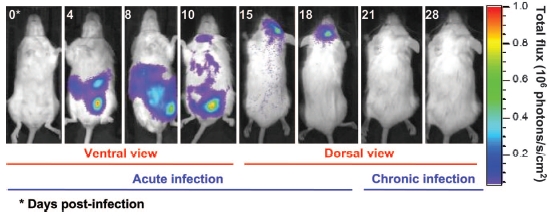

Vyasís group labelled the parasites they used in their study with a bioluminescent molecule called luciferase, enabling them to visualize how it spreads through the body during the course of infection. This showed that it initially infects peripheral tissues before making its way to the brain. 1 month after infection, T. gondii was no longer detected in peripheral tissues, but was found solely in the brain. Dissection of the rodentís brains showed that the parasite had formed cysts in a variety of brain regions, including the olfactory bulb hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, all of which have previously been shown to be responsive to cat odour, as well as several other regions that are unresponsive to cat odour. But the greatest densities of cysts were found in the amygdala, a region of the limbic system involved in the encoding of fearful memories. (The image at the top shows a cyst formed by T. gondii in brain tissue.)

So, T. gondii not only targets the neural circuitry involved in fear, but it also alters a specific response mediated by that circuitry. Exactly how remains unclear, but it is likely that the parasite synthesizes chemicals that mimic the rodentsí own neurotransmitters. These chemicals apparently manipulate the rodentís response to cat urine by perturbing the neurochemistry of the amygdala and connected structures. Specifically, the authors speculate that T. gondii has an effect on neuromodulation mediated by the transmitters dopamine and noradrenaline.

But the plot thickens, and takes a somewhat sinister turn. T. gondii can infect most species of warm-blooded animals, including humans, who may become infected by coming into contact with cat faeces or by eating undercooked meat. It is estimated that some 40% of the worldís people harbour the parasite, and that up to 80% have been infected at some time in their life. In people with a compromised immune system, such as AIDS patients and pregnant women, toxoplasmosis, the disease caused by T. gondii infection, can, in some cases, be fatal (this is why pregnant women are told to stay away from cat litter). But in the vast majority of people, T. gondii infection results is asymptomatic.

Or so it would seemÖ

A number of recent studies have suggested that T. gondii can cause subtle changes in the personalities and behaviour of infected people. Last year, for example, Jeroslav Flegr, a parasitologist at Charles University in Prague, found that women infected with the protozoan are more likely to give birth to boys than to girls. Thus, by influencing the boy-to-girl birth ratio, T. gondii may have a considerable effect on the human population. Flegr also administered a battery of psychological tests to infected and uninfected people, and compared the results. His preliminary data suggest that T. gondii can alter the behaviour of humans as well as that of rodents. Nicky Boulter, a research fellow at the Institute for Biotechnology of Infectious Diseases, at the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia, summarizes the findings:

"Infected men have lower IQs, achieve a lower level of education and have shorter attention spans. They are also more likely to break rules and take risks, be more independent, more anti-social, suspicious, jealous and morose, and are deemed less attractive to women. On the other hand, infected women tend to be more outgoing, friendly, more promiscuous, and are considered more attractive to men compared with non-infected controls. In short, it can make men behave like alley cats and women behave like sex kittens."

Epidemiological studies have also implicated T. gondii in some cases of schizophrenia. This is particularly interesting, especially when we consider the speculations of Vyasís group about how the parasite manipulates neural circuitry in the amygdala. Because both dopamine and noradrenaline have also been implicated in schizophrenia, it seems plausible that any link between T. gondii and schizophrenia would likely be linked to the organismís ability to alter the levels or activity of these neurotransmitters. Finally, Kenneth Lafferty, a biologist with the U. S. Geological Survey, has also found a positive correlation between of T. gondii infection and levels of neuroticism. But he goes so far as to suggest that the aggregate (or cumulative) effects of T. gondii infection in millions of people may have a major effect on collective personality, and could, therefore, subtlly influence human societies and cultures.

For more about Toxoplasma gondii, read this post by Carl Zimmer, and follow the links in it.

References:

Vyas, A., et al. (2007). Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors. PNAS doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608310104. <[a href="http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/0608310104v1" modo="false">Abstract]

Lafferty, K. D. (2006). Can the common brain parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, influence human culture? Proc R. Soc. B. 273: 2749-2755. <[a href="http://www.bec.ucla.edu/papers/Lafferty_10.2.06.pdf">Full text]

Torrey, E. F. & Yolke, R. H. (2003). Toxoplasma gondii and Schizophrenia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9: 1375-1380 <[a href="http://origin.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol9no11/pdfs/03-0143.pdf" modo="false">Full text]

Article posted at Neurophilosophy