Key words :

future energies,

texas

,peak oil

,saudi arabia

,russia

,jeffrey brown

,venezuela

,national oil companies

,north sea

,pemex

Do Texas and the North Sea Foretell the Future of Oil Production?

25 Feb, 2010 12:22 pm

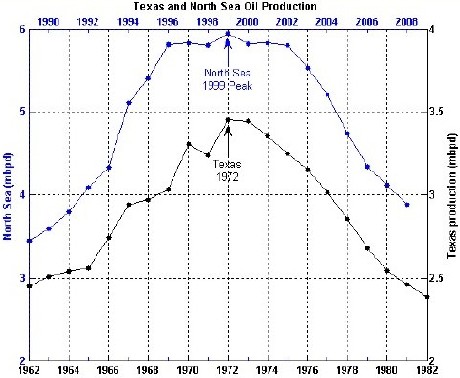

Oil supply optimists claim that new technology combined with private development of the world's remaining oil resources--most of which are now under the control of government-owned companies--would vastly increase global oil production and put off any decline for decades. Texas oilman Jeffrey Brown isn't buying it, and he cites the history of oil production in Texas and the North Sea to explain why.

|

Chart Courtesy of Jeffrey Brown

Oil supply optimists don't have to think very long to findplenty of examples of government-owned oil companies that have failed to keep pace with technology, engaged in lethargic exploration and development of their oil resources, and/or purposely restricted production. The aim of OPEC, after all, is explicitly to limit production to maintain prices in the international oil market. Saudi Arabia, the largest producer in the cartel, keeps hundreds of thousands, if not millions of barrels of oil that it could produce off the market.

Pemex, the Mexican national oil company, has done such a poor job in developing new capacity that its production has declined from more than 3.8 million barrels per day in 2004 to just under 3 million per day in October 2009, the latest month for which figures are available. Venezuela has deposits of heavy oil thought to rival the huge conventional deposits of Saudi Arabia. Yet the country's overall production is down from 2.9 million barrels per day in 2004 to just under 2.5 million barrels in October 2009. The sorry state of the Russian oil infrastructure, the renationalization of part of the Russian oil industry, heavy taxation of oil have all served to keep a lid on Russian oil production at around 10 million barrels a day.

Given this record it would seem that private development of these resources would provide incentives for improving the infrastructure, lead to increased exploration and production, and apply the best available technology. But would such a move actually overcome the recent worldwide plateau in production and create the glut of oil that the optimists predict?

Texas oilman Jeffrey Brown doubts it. Brown is also known in oil circles for his Export Land Model which suggests that declines in oil available for export over the next decade or so will create enormous problems for importing nations. The first thing one has to know about current conventional oil supplies is that about 60 percent of them come from 500 so-called giant fields, that is, fields containing more than 500 million barrels of oil. The top 20 fields produce 25 percent of the world's total. The problem is that production from giant fields is declining overall. Many of these fields are more than 50 years old, and very few giants have been discovered in recent decades. (For a good discussion of giant oil fields and production, see "Giant oil field decline rates and their influence on world oil production.")

Experience shows that once giant fields turn down in any oil producing area, subsequent and usually smaller discoveries do not make up for the decline, contends Brown, a Dallas-based independent petroleum geologist who manages a joint-venture exploration program. Brown says that private development, new technology and unlimited access to drilling--the desiderata of the oil optimists--can realistically only soften any decline in oil production. And, he cites as his evidence the experience of Texas and the North Sea, two areas where private development was combined with the best available technology and virtually unlimited access to drilling.

"You tend to find the big oil fields first," Brown says. And, that's precisely what happened in Texas and the North Sea. Texas peaked in 1973 and the North Sea in 1999. And, despite the application of the best available technology for both exploration and production, despite virtually unlimited access to prospective areas, and despite entirely private development under free market conditions, production sank year after year. And, lest readers think that these two areas don't represent a very big sample, Brown explains that these two oil provinces alone represent 9 percent of cumulative world production to date.

"If all our bag of tricks did was slow the rate of decline, why would it be different in any other post-peak place in the world?" Brown asks. And, when he says "post-peak," he is talking about all those giant and supergiant oil fields that have already seen their rate of production turn down.

Brown's not saying that better technology, private development and better access won't allow the world to pump more oil than it otherwise would have. He's just skeptical that these things by themselves can ultimately overcome the enormous losses currently being experienced in the giant fields that are past peak or those that soon will be. And, that means that even if the optimists could wave a wand and make conditions ideal worldwide for oil development from this day forward, it might not save us from a nearby peak in world oil production followed by a relentless decline. We have only to look at Texas and the North Sea to understand why.

Key words :

future energies,

texas

,peak oil

,saudi arabia

,russia

,jeffrey brown

,venezuela

,national oil companies

,north sea

,pemex

-

12/12/12

Peak Oil is Nonsense Because Theres Enough Gas to Last 250 Years.

-

05/09/12

Threat of Population Surge to "10 Billion" Espoused in London Theatre.

-

05/09/12

Current Commentary: Energy from Nuclear Fusion Realities, Prospects and Fantasies?

-

04/05/12

The Oil Industry's Deceitful Promise of American Energy Independence

-

14/02/12

Shaky Foundations for Offshore Wind Farms

Read more

Read more

This was true when John, D; Rockefeller created the integrated petroleum company back in the late 19th century but rendered obsolete by the increased efficiency of consumption. Oil has more value as a form of currency - one that every aspect of modernity requires - than as a physical enabler for commerce.

High prices are self reinforcing and at the current $80 level would simply shut in any excess production that appeared - even if such added production is possible. This in fact seems to be taking place right now as Saudia and other countries with surplus production jockey for the right to be swing producer.

It is the fantasy that new finds translate automatically into lower prices that needs to be dissipated. The new model is steady price, more economic damage leading to lower nominal prices but higher real price of the oil input relative to other inputs.

What is positive about this development is that the substitution of petroleum powered automation is becoming uncompetitive. This makes human labor a relative bargain..

"the problem is NOT that we're going to run out of oil; the problem IS that we're NOT going to run out of oil before suffocating in the debris of the oil economy".

If only it were true that we'd run out of oil, our problems would be solved; the price will rise, and alternative fuels would take the place of oil.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment. First, please note that I say nothing about "the end of oil." The problem is not that oil is going to run out, but rather than its rate of production is set to decline, exactly when we don't know. And, our infrastructure and society will simply not be ready for such a change should it occur within the next decade or so. What I'm talking about is what's often called the rate-of-conversion problem which implies that we will be trying to build an alternative energy economy while the overall amount of energy available to society is declining, a herculean feat that has enormous political and social implications.

Second, I think that your view of oil economics is too simplistic. We've already seen that oil prices above $100 a barrel are prone to put the economy into tailspin, one that has meant a rapid decline is exploration and development expenditures in the oil industry, but particularly in those projects such as the oil sands and heavy oil recovery that are only profitable at high prices. There has also been a swoon in investment in alternative energy sources which belies the notion that high oil prices automatically create conditions favorable to the expansion of alternative energy. Just the opposite has proven to be the case because of the effect of high oil prices on the economy. While no one can know the future, the idea that oil--at least while it still provides the bulk of the world's primary energy--could reach $500 a barrel, let alone $1,500 on a sustained basis without bringing down the economy as a whole seems fanciful at best.

Furthermore, we must acknowledge the Law of Receding Horizons. All of the alternatives to conventional oil including those locked in the tar sands and in oil shale currently require oil to process. They may also require natural gas and coal as in the case of ethanol. The key point is that the cost of oil alternatives rises along with oil; we have a moving target and thus the Law of Receding Horizons. You are correct that there are large resources of oil or oil-like substances (kerogen from deceptively named oil shale) but the cost of getting at these resources both in terms of energy and money are very high and move higher as fossil fuel prices escalate. In addition, the rate at which these unconventional oil resources can be brought to market is currently quite limited and is likely to remain so. The highest estimate of oil production from the Canadian oil sands in 2030 is 5 million barrels per day. Sounds like a lot, but not when compared to a projected total worldwide liquids production of 105 million per day. (I am personally doubtful we will be producing 105 million barrels a day by 2030, but only predict that it will be less.) The U. S. Energy Information Administration forecasts only 140,000 barrels a day of production from oil shale by 2030 with U. S. demand alone for total liquids set to rise to 22 million barrels per day. The rate of production from such unconventional sources will likely not be able to keep up with depletion.

Of course, we can wait and see and hope that the market will not crush the economy and therefore expenditures on alternatives repeatedly. Or the world could adopt a pre-emptive strategy focused on getting overall energy consumption down dramatically so that we are no longer subject to the vagaries of the international oil market.