Can Renewables Replace Fossil Fuels?

23 Nov, 2009 11:57 am

With peak oil already upon us, sustaining oil supply is akin to running up a down escalator. Or, as Nate Hagens put it at the ASPO peak oil conference earlier this month, ?Technology is in a race with depletion and is losing (so far).? The urgent question then is: Can renewables fill the gap of oil depletion?

|

The most recent global data summarized by fuel available from the EIA is, unfortunately, for 2006 and only preliminary (I know they’re trying to improve their reporting but seriously, they need to do better than that), but we’ll use what we’ve got.

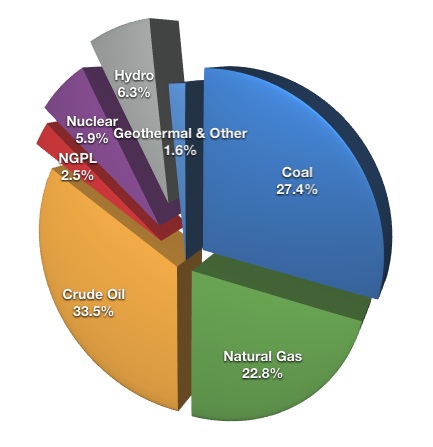

In 2006, the total amount of energy the world consumed was 469 quadrillion BTUs, or quads.* Charted in percentage terms, the global fuel mix looks like this:

|

| World Primary Fuel Mix, 2008. Chart by Dave Waldorf. Data source: EIA Annual Energy Review 2008 (released June 2009) |

If the latest information I gathered at the ASPO peak oil conference is correct–and I think it is, or at least is as close to correct as anybody is going to come at this point–then we should expect oil to begin declining at about 5% per year starting around 2012 – 2014.

Of the 157 quads provided by oil, at a 5% decline rate we’ll lose 7.85 quads per year, or 1.7% of the world’s primary energy supply.

The “Geothermal and Other” category, supplying 1.6% of the world’s primary energy, represents all the renewable sources combined: geothermal, solar, wind, biomass, and so on.

Since 1.7% is very close to 1.6%, we can put the challenge of substituting renewables for oil this way: Starting around 2012 – 2014, the world will need to build the equivalent of all the world’s existing renewable energy capacity every year just to replace the lost BTUs from oil.

Fortunately renewable energy of all kinds is enjoying a massive growth spurt, attracting trillions of dollars in investment capital. On average, the sector seems to be growing at about 30% per year, which is phenomenal…but it’s not 100%.

In terms of BTU substitution, then, it seems unlikely that renewables can grow at the necessary rate.

Not Just BTUs

However, the challenge is more complex than mere BTU substitution.

Replacing the infrastructure, particularly transportation, that’s based on oil with one based on renewably generated electricity will in itself require energy–and lots of it. As Jeff Vail, an associate with Davis Graham & Stubbs LLP, said at the conference, between 80-90% of the energy inputs for renewables must be made up front, before they start to pay any energy out.

Even if renewables were able to make up all of the lost energy from oil, still more would be needed to afford any economic growth.

In all it seems a fair bet that it will take at least a decade for renewables to merely catch up with the annual toll of oil depletion. The gap will likely manifest as fuel shortages in the OECD when the developing world outbids it for oil, and a long economic recession or depression…unless efficiency comes to the rescue.

To that point, Vail speculated that population increase alone could offset as much as 30% of the improvement in conservation and efficiency. He noted that despite the recession, car sales are up 29% in India as people buy their very first cars.

Falling Net Energy

Another driver of the down escalator is that the net energy (EROI, or energy returned on energy invested) of nearly all fossil fuel production is falling.

Dr. Cutler Cleveland at Boston University has observed that the net energy of oil and gas extraction in the U.S. has decreased from 100:1 in the 1930’s, to 30:1 in the 1970’s, to roughly 11:1 as of 2000.

Simply put: As the quality of the remaining fossil fuels declines, and they become more difficult to extract, it takes more energy to continue producing energy.

This begs the question: What EROI must the replacements have to compensate for oil depletion?

Vail presented several models attempting to answer it. In his optimistic scenario, assuming a 5% rate of net energy decline and an EROI of 20 for the renewables, the “renewables gap” was filled in year 3. In his pessimistic scenario, assuming a 10% rate of net energy decline and an EROI of 4 for the renewables, the gap wasn’t filled until year 7.

For a sense of how reasonable those assumptions are, we must turn to the academic literature, since no business or government agency has yet shown any particular interest in EROI studies (much to my dismay).

Studies assembled by Dr. Charles Hall (source) put the average EROI of wind at 18 (Kubiszewski, Cleveland, and Endres, 2009); solar at 6.8 (Battisti and Corrado, 2005), and nuclear at 5 to 15 (Lenzen, 2008; Hall, 2008). No data is available for geothermal or marine energy. All the biofuels are under 2, making them non-solutions if the minimum EROI for a society is indeed 3 (Hall, Balogh and Murphy, 2009).

[A quick aside: The huge range of the nuclear estimate is one indication of how difficult it is to accurately asses the costs of nuclear, which is part of the reason I still haven’t written the article I know many of you are hoping to see some day. I’m working on it, and still looking for current research with appropriately inclusive boundaries and updated numbers. Nearly everyone is still using cost estimates that predate the commodities bull run, not even realizing how it distorts their analysis. So far I have found nothing to change my outlook that the nuclear share of global supply will stay roughly the same for several decades.]

I am not aware of any studies on the EROI of biomass not made into liquid fuels–for example, methane digesters using waste, landfill gas, and so on–but its sources and uses are so varied that if the numbers were available, they probably wouldn’t be very useful. While such applications are generally good, they’re not very scalable—they work were they work, and don’t where they don’t.

Theorem of Renewables Substitution

Where EROI analysis leaves us is unclear; it needs more research and a great deal more data. There are some useful clues in it though.

First, we know that biofuels–at least the ones we have today–won’t help much, other than providing an alternate source of liquid fuels while we’re making the transition to electric.

Second, we know that solar tends toward Vail’s pessimistic scenario, and wind fits the bill for his optimistic scenario.

But here’s the rub: The lowest EROI source, biofuels, is the easiest to do, with the vigorous support of a huge lobby and Energy Secretary Chu himself. Rooftop solar is the next-easiest to do but making up the lost BTUs takes longer due to its moderate EROI. And the source with the highest EROI, wind, is the hardest. (I explained why solar is easier here.)

Therefore I propose the following, slightly snarky Theorem of Renewables Substitution: The easier it is to produce a source of renewable energy, the less it helps.

The Winner: Efficiency

All of these factors–the declining supply, the pressures of the developing world on demand, the renewables gap, and the theorem of renewables substitution–underscore how crucial efficiency is to addressing the energy crisis.

It also underscores how profitable the entire energy sector will be for many, many years to come.

With supply maxed out, and demand at the mercy of a developing world, the name of the game now is doing more with less. More efficient vehicles and appliances, building insulation, co-generation…and all the other ways to eliminate waste.

I know it doesn’t have the sex appeal of, oh, say space based solar power, but it’s where the real gains will be made.

*The thermal values (heat content) of various fossil fuels are typically measured in BTUs. One BTU is roughly equivalent to the heat produced by burning a wooden kitchen match. One cubic foot of dry natural gas contains approximately 1,031 BTUs. For those who prefer their data measured in joules, 1 quad = 1.055 exajoules (EJ, or 1018 joules). Renewable energy, however, is typically measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh), or the amount of energy delivered by a one-kilowatt source over the course of an hour. 1 kWh = 3412 BTUs.

Originally published on GetRealList

-

12/12/12

“Peak Oil” is Nonsense… Because There’s Enough Gas to Last 250 Years.

-

05/09/12

Threat of Population Surge to "10 Billion" Espoused in London Theatre.

-

05/09/12

Current Commentary: Energy from Nuclear Fusion – Realities, Prospects and Fantasies?

-

04/05/12

The Oil Industry's Deceitful Promise of American Energy Independence

-

14/02/12

Shaky Foundations for Offshore Wind Farms

The problem is low cost primary energy.

But if you can get the cost to GEO to $100/kg or less, then 2 cent per kWh electric power just falls out of the economic model.

Google henson oil drum or for a more recent paper given at the Beamed Energy Propulsion conference, ask by email. hkeithhenson@gmail.com

The title is misleading, since it focuses only on EROI. Other issues also have to be included, such as local acceptance and intermittency. We don't have a solution to the problem of intermittency, but if we did the EROI for renewables would certainly be lower. Altering the projects for the sake of local acceptance will also lower the EROI.

I think we're suffering here from the Tyranny of the Average. We know that the EROI on different projects varies widely. Economics and common sense dictate that the projects with the best EROI (or near the best) will be chosen for a given situation, so we don't have to decide on the basis of average EROI. We ought to be proceeding on parallel paths; in the near term we can see big improvements with the high-EROI options while we are working on solutions with greater results in the long term.

Your net conclusion, that efficiency is the most potent solution available, fits everything I've read on this topic. On the question given in the title, I think a broader view is needed. Clean energy, including nuclear, can replace fossil fuels but only if concerted, global efforts are made, on the order of a general mobilization. If World War II decisions had been driven by EROI, the Nazis would have won. Is climate change a lesser threat?