Jeffrey Brown and the Net Oil Exports Crisis

6 Mar, 2009 11:54 am

With peak oil comes peak oil exports. Why Texas oilman Jeffrey Brown thinks the world is headed for a drastic energy downsizing and soon.

"Low single-digit decline rates, that's what people [concerned about the peaking of world oil supplies] have been thinking about," Brown told me in a recent phone conversation. But he wondered what such decline rates for world oil production might mean for oil exports and by definition for the oil importers dependent on them.

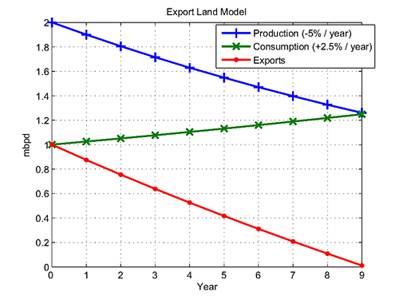

His pondering led to the creation of the the Export Land Model. It goes something like this: A hypothetical oil exporter--let's call it Export Land--has reached its peak in oil production. Assume domestic users consume half of all the oil produced in Export Land at the moment; assume a 5 percent annual decline rate for production; and assume a 2½ percent annual increase in domestic consumption. The result is that Export Land reaches zero exports in an astonishingly short nine years.

|

"Only 10 percent of all post-peak production is exported [from Export Land]," Brown notes. "I was flabbergasted at how quickly exports went to zero."

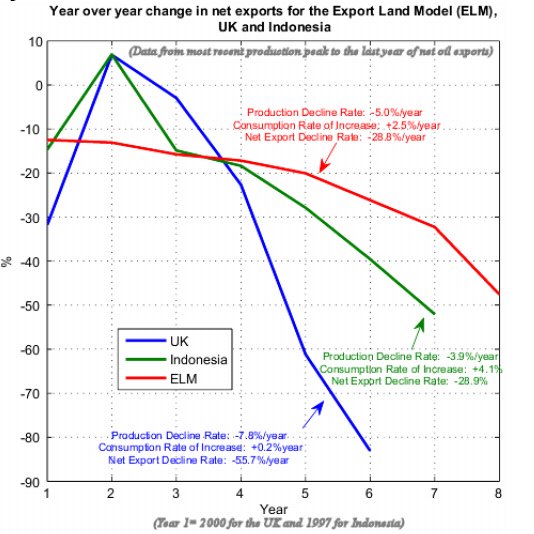

Ok, so does the model have any real world significance? Brown and his fellow number cruncher, Samuel Foucher, a computer researcher, looked at two seemingly disparate cases, Indonesia, a developing country with a high growth rate for domestic oil consumption and a low production decline rate and the United Kingdom, a developed country with almost no increase in consumption, but a high decline rate. Indonesia went from peak oil production in 1997 to zero exports in 8 years. The U. K. went from peak production in 2000 to zero exports in 7 years.

|

The countries also represent extremes in policy. The U. K. had high energy taxes. Indonesia subsidized energy consumption. But despite the differences, their time to zero exports was very similar. Brown surmises that the most important factor in the length of time to zero exports is the starting point for domestic oil consumption. Both countries were consuming between 50 and 60 percent of their own oil production at peak.

Using insights gained from this exercise, Brown and Foucher set about examining the possible future of oil exports from the world's top five exporters: Saudi Arabia, Russia, Norway, Iran and the United Arab Emirates. Between them they produce about half of the world's net oil exports. Norway and Iran are already demonstrably past peak production. Russia is now declining. Saudi Arabia has not exceeded its peak in 2005 on a sustained basis, but the jury is still out. The situation is unclear for the UAE.

Brown and Foucher, for the purposes of their model, assume that all countries are at or near peak production. If the team's middle case for production and consumption holds, then net exports from the current top five exporters will dwindle to zero by 2031. The period of time is longer than that for the Export Land Model because at 25 percent the combined initial domestic consumption of the five countries as a percentage of their production is much lower than that of Indonesia or Great Britain.

Stopping points along the way illustrate the problem more clearly. Since 2005, the top five oil exporters have exported 20 percent of all post-peak exports based on Brown's and Foucher's calculations. By the end of 2012, the two expect that half of all exports will have arrived on foreign shores. The percentage of cumulative exports rises quickly right after peak because that is when production is at its highest and therefore when the most oil is available for export.

It is hard to see how the world could work as it does today in the decades ahead given such numbers. Of course, oil production could miraculously grow from here, but Brown just doesn't see how. Looking at a measure called crude oil plus condensate--what we normally think of as conventional oil as opposed to total liquids which includes ethanol, tar sands production and natural gas liquids--he says that the billions of dollars spent by the world's oil companies on exploration and drilling could not prevent a cumulative shortfall in conventional oil production from 2005 onward. And, with the recent slump in oil prices, investment in exploration and drilling has plummeted. Without that new investment, he thinks it is likely that the peak in world oil production is already in. The oil industry is now too far behind the curve and depletion will keep the industry on an ever-accelerating treadmill.

Well, what about demand? Isn't falling demand, which is a consequence of the ongoing financial crisis, going to ease the pressure on oil supplies and delay the day of reckoning? Not really, according to Brown. He looks back to the 1930s for some guidance. Even during the Great Depression worldwide oil consumption fell in only one year, 1930. After that it rose every year. And, so did prices, on average 11% percent per year from 1931 through 1937 (measured in constant dollars). By 1937 there were 3 million more cars on American roads than at the beginning of the decade which accounts in part for the pressure on oil prices.

But there are important differences between now--Brown believes a depression is currently unfolding--and the previous depression that actually bodes ill for oil supplies and prices. First, instead of expanding rapidly as oil production did in the 1930s, production is now stagnating and will perhaps decline as exploration and drilling efforts continue to plummet. Second, the world today has not just millions of people wanting to become car owners, but hundreds of millions, located mostly in Asia. Many still have the means to pay and will probably continue to buy cars, adding significantly to oil demand even during this economic downturn.

With supplies constrained for geologic and investment reasons, Brown expects net oil exports to continue their decline and create a bidding war among importers similar to the one that vaulted oil prices to almost $150 a barrel last summer. He thinks it is possible that the average oil price for 2009 could very well be the same as in 2008, around $100 a barrel. The average, he says, not the wild swings, are a much better indication of what people are paying for oil in the course of a year.

And so, the net oil exports crisis only looks to get worse. He points to the Indonesian example. "Indonesia had a fall [in oil exports] in '97, a pickup in '98 and resumed its decline in '99," he explained. "After only two years [of post-peak production, i.e. 1997 and 1998), the country had shipped 44 percent of all the cumulative oil it was ever going to export post-peak." In other words, declines in net exports tend to worsen dramatically in a short period of time.

Despite his gloomy outlook on oil supplies, Brown strikes a hopeful note. He thinks the world can manage the needed downsizing once people abandon their faith in the myth of perpetual economic growth. Having done that, they can band together with their neighbors and fellow citizens and create a new low-energy society that he believes could end up making us healthier--we'll have to walk and bicycle more--and more connected to our neighbors with whom we'll have to work closely to make our communities work.

-

12/12/12

Peak Oil is Nonsense Because Theres Enough Gas to Last 250 Years.

-

05/09/12

Threat of Population Surge to "10 Billion" Espoused in London Theatre.

-

05/09/12

Current Commentary: Energy from Nuclear Fusion Realities, Prospects and Fantasies?

-

04/05/12

The Oil Industry's Deceitful Promise of American Energy Independence

-

10:00

Shaky Foundations for Offshore Wind Farms

Read more

Read more